by Rob Halliday

When I was very much younger, just starting out playing with moving lights, there were two things I assumed were true. Firstly, that one moving light would behave the same as another, so you could swap one out without having any effect on the show. Secondly, that my memory was good enough to keep track of what all of the lights did during the show not just in tech but when returning months or (hopefully) years later.

Turns out, neither of those things are true. Even lights of the same kind often display subtle differences, particularly with edge focus, shutter shape or gobo orientation. Tiny rigging differences can lead to large position differences when magnified by long throws. And one's memory isn't as good as one hopes, and gets no better with age...

With conventional lights, we've always had to record a light's focus in order to accurately maintain or re-create it. American associate lighting designers specialise in exactly this - 'hotspot 6L@+3' plus perhaps a little sketch.

Of course, each conventional only has one focus. Moving lights have many. Their motors mean they can attempt to get back to those focuses - put the lights in the same positions in a new venue, load the disc and you'll get a fair approximation of the lighting. But the devil is in the detail - is the edge just as it was, are the shutters exactly right? If the rig isn't hanging in exactly the same place, more fixes will be needed. Have to change to a different type of light and the challenge becomes even greater.

All of which leads to the conclusion that if a show is going to have any kind of life, the moving lights need to be focus plotted just as much as the conventionals - perhaps more, since an incorrectly focussed conventional is wrong once, an incorrectly set moving light wrong many times. An accurate record is good for me as the programmer, great for the crew I hand a show over to, and fantastic for the lighting designer - a permanent record of the show for their archive.

In America, land of paperwork, this has traditionally been achieved by employing a moving light tracker - someone sitting next to the programmer, manually recording each focus. In part this was through necessity: the early Vari-Lite Artisan console gave little feedback, with no "1@50, down centre" channel display. You really had to write things down if you needed to edit the show later.

Later consoles seemed to change the approach required. The screen would show what each light was meant to be doing, particularly if preset focuses were clearly named. I could certainly remember the actual focus through the tech process. Given that, notating hundreds of focuses that might end up not being used seemed wasteful - as did pausing to write things down during the tech, usually the most time-constrained period of getting a show on.

My approach became to concentrate on programming the show then, when nearly done, to take the showfile into an off-line editor and manually work through it light by light, making a note of which light used which focus. It was tedious and time consuming, and every time I did it I thought "aren't computers meant to save us from this kind of dull, repetitive job?" But there was always a deadline, and it always seemed safer to just get the job done than try to figure out a better way of doing it.

List in hand, we'd then work through each light's focuses, recording them firstly (circa 1997) with sketches and descriptions, later (from circa 2001) with digital photographs. It was a frustrating task: there's a sense of progress to focus plotting a conventional rig, start at channel 1, go to channel 200, job done. With moving lights you start at 1, go to 30, then start again. And again. And again.

Which is why finally, on some big show with time to spare, I started exploring alternatives. This was the start of FocusTrack.

The aim was to take the showfile from the console and have a computer figure out which focus positions each light was used in. 'Used' turned out to be a tricksy word: it first meant 'in this position with the light actually on', and later evolved to include 'moving from this position as a light is fading in, or to this position as fading out', since in both cases the position is part of the overall look of the show. Along the way I realised that the same test was useful for more than just position - which scroller colours or moving light gobos were actually used?

FocusTrack can now achieve all of those things and more.

So, how do you use it? In effect, you get your showfile data out of your console (ETC Eos family, MA grandMA or Strand 500-series) then tell FocusTrack to import that data. You specify the cue lists or cue range you're interested in, and a minimum level you consider on (so cues where lights are just pre-heating don't get counted). FocusTrack then ponders things for a while - seconds for small shows, possibly hours for really big shows in which case you set it to work and go to dinner, or to bed.

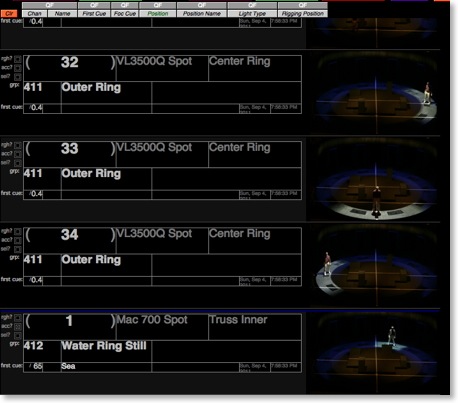

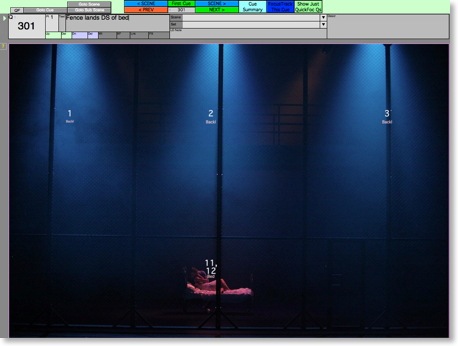

Import complete, you get three sets of information. Cue List shows you your cues from the console, but with space to add more information and the ability to better reveal the structure of the show by highlighting the start of scenes, and to show or hide cue parts. RigTrack has the information about your rig - channel 4 is patched to address 308 and is a VL3000; you can add other information to this ('rigged on LX4') either by hand or by importing from Lightwright, VectorWorks Spotlight or other sources. FocusTrack lists each position that each light is actually used in. On big shows that seems to average about 12 positions per light, so with 50 lights that might be 600 of what I call 'lamp-focuses'. If you add more information to Cue List - when scenes start or scenery appears on stage - FocusTrack can cross-reference this to work out which lamp-focuses are used in particular scenes or with particularly scenery.

This means you now know how each light is used. But you'd still want to create a record of what each light actually looked like in each position. FocusTrack helps with this by talking to the console and your camera: run on a Macintosh, it can turn each light on in each position and then tell you to take a picture or just trigger the camera directly. The process of photographing each focus becomes incredibly fast because you're not having to look up the information then tell a console operator which light to bring up, with all of the possibilities for error in that process. Big shows regularly take 1500 or more pictures in an eight hour session - averaging a photo every 15 seconds, including waiting for scenery to be shifted and, ideally, for someone to move into the light as a reference for direction and angle. You can add pictures of whole washes, of conventional focuses, and of cues, to give you a complete record of every building block of the lighting and the end result.

You can then access that information however you like - by channel when swapping out a light, by scene or set during rehearsals, or even by cue. This is great when checking a show over a dress run (or a first night on tour!), FocusTrack walking you through the focus either listing every light in every cue or just focuses the first time they appear, since the next time you'll hopefully already have got the focus fixed.

It can also help you prepare for that tour: because it has the whole showfile behind it, it can tell you which lights never come on (so you can cut them), which colours and gobos are used (so you can shrink your scrolls or try different colours), and which focuses for a light are similar or identical to other focuses (allowing you to merge focuses to make updating everything in each venue speedier). It can even have a reasonable stab at calculating power loads per cue or power consumption through the show. As it evolves, new tools have appeared - a way of notating focuses by cue as you make them if you want to work 'American' style, or generating summaries of what cues actually do ('blue backlight gets brighter, red crosslight goes out') which opera and ballet designers crave when re-creating shows in new venues with completely different rigs. Plus it has a selection of tools for managing the rig once it's up and running - tracking faults and maintenance on fixtures, lamp-hour totals and more.

It is by no means perfect, but I think it's an interesting and useful tool that is invaluable on shows that have - or hope for - a long life. If you're interested, it's available for you to download and try for yourself.